Overview

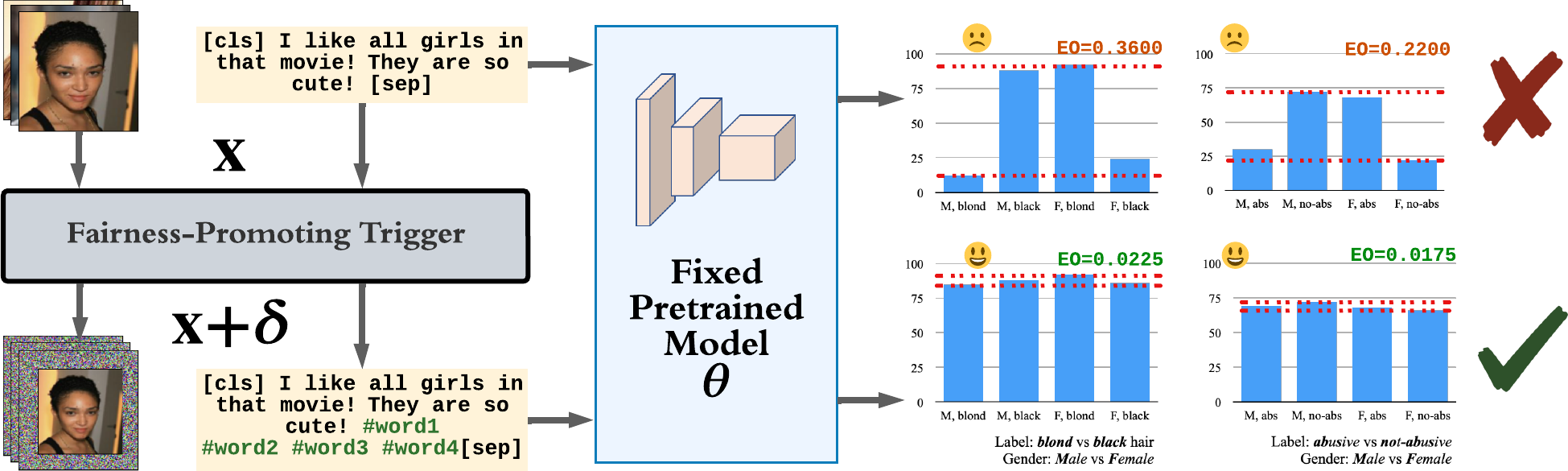

In this paper, we propose a new generic fairness learning paradigm, called fairness reprogramming:

Principal Research Question

If so, why and how would it work?

Fairness Reprogramming

Consider a classification task, where

The goal of fairness reprogramming is to improve the fairness of the classifier by modifying the input

- Equalized Odds:

- Demographic Parity:

where

Fairness Trigger

The reprogramming primarily involves appending a fairness trigger to the input. Formally, the input modification takes the following generic form:

where

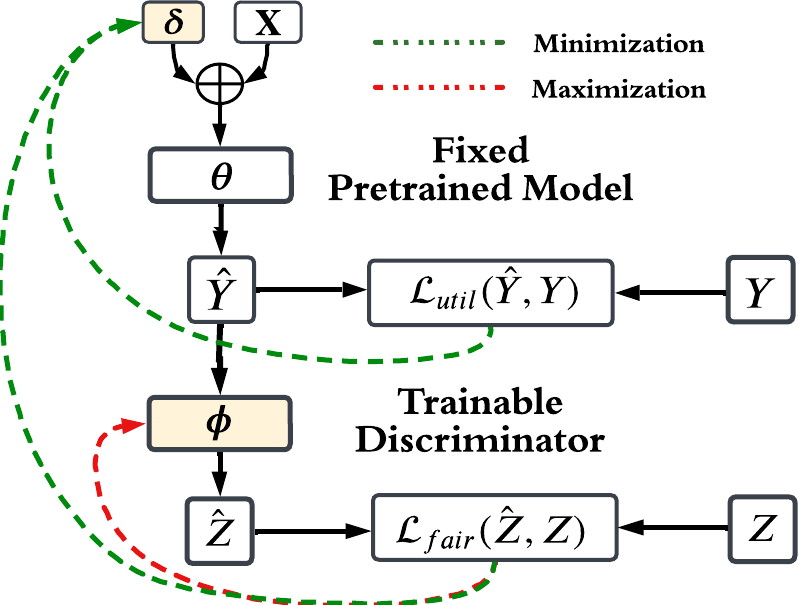

Optimization Objective and Discriminator

Our optimization objective is as follows

where

The second loss term,

We give an illustration of our fairness reprogramming algorithm below, which co-optimizes the fairness trigger and the discriminator at the same time in a min-max fashion.

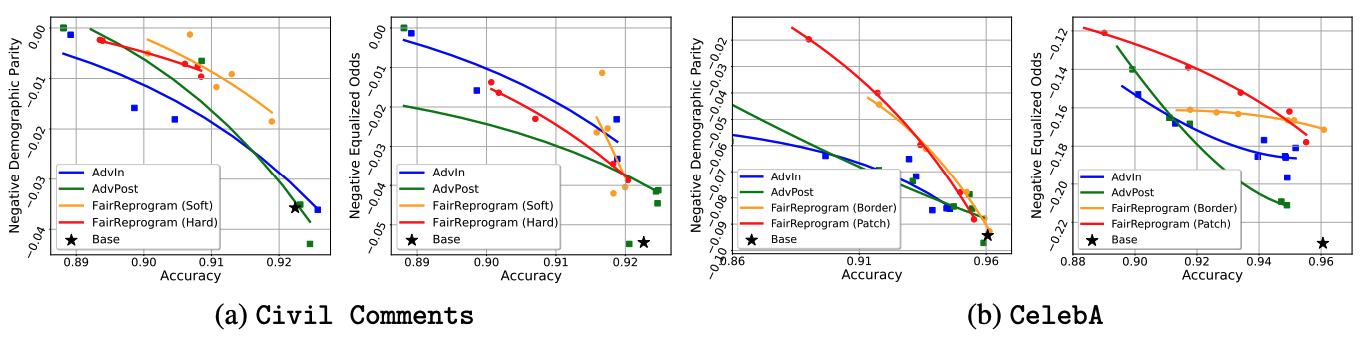

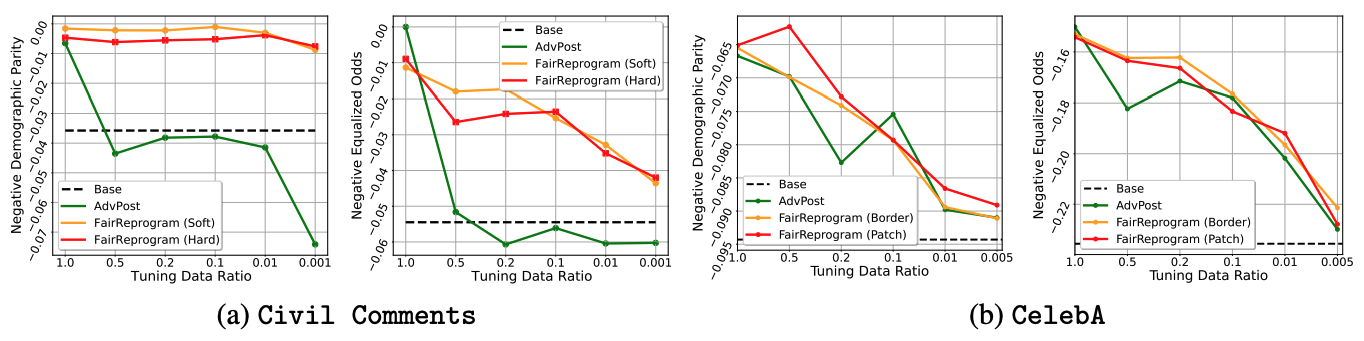

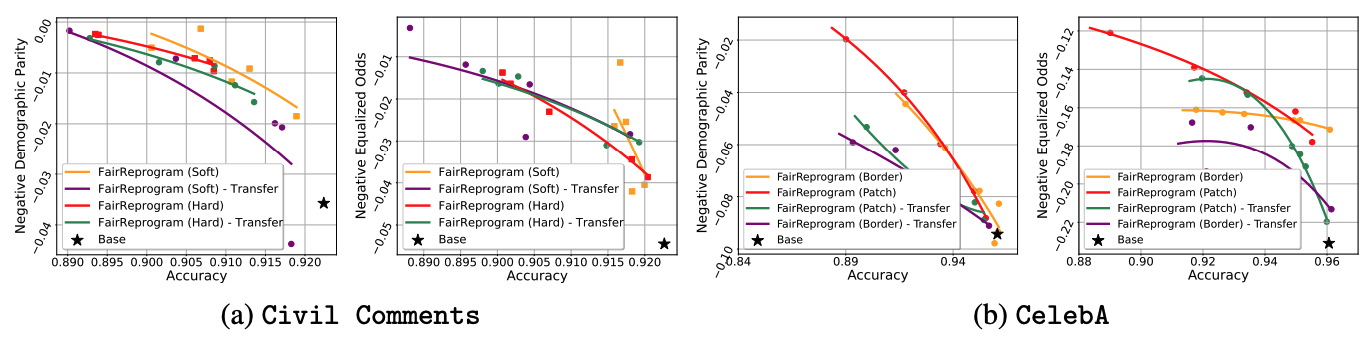

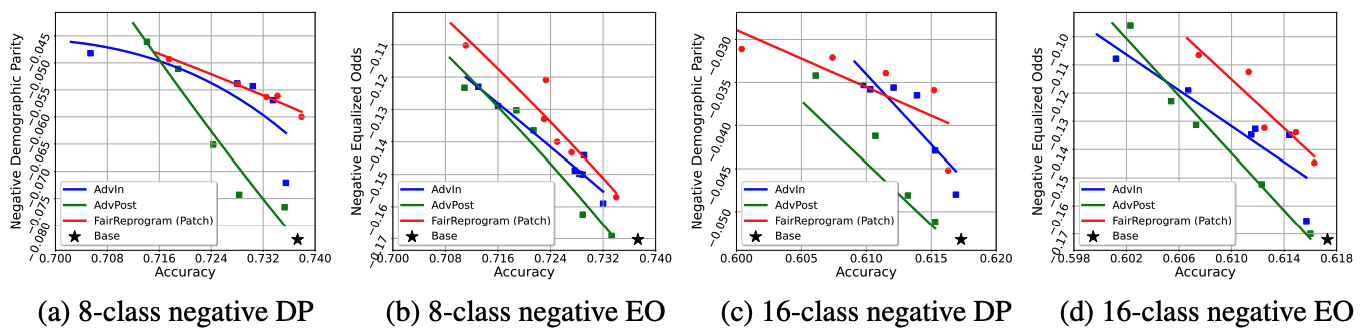

Experiment results

We consider the following two commonly used NLP and CV datasets:

-

Civil Comments: The dataset contains 448k texts with labels that depict the toxicity of each input. The demographic information of each text is provided.

-

CelebA: The dataset contains over 200k human face images and each contains 39 binary attribute annotations. We adopt the hair color prediction task in our experiment and use gender annotation as the demographic information.

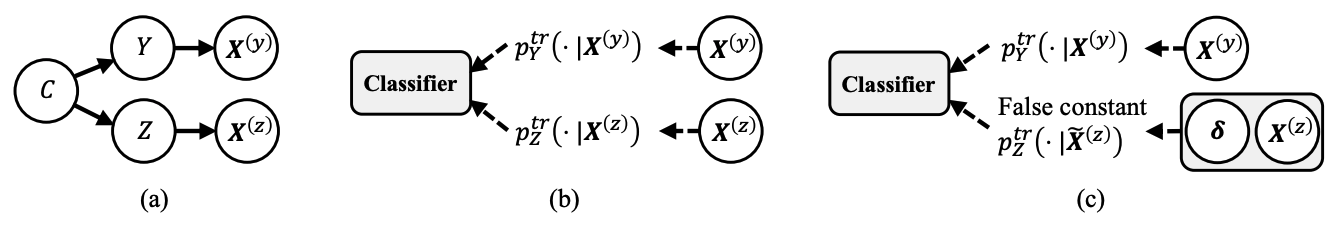

Why does Fairness Trigger work?

In our paper, we both theoretically prove and empirically demonstrate why a global trigger can obscure the demographic information for any input. In general, the trigger learned by the reprogrammer contains very strong demographic information and blocks the model from relying on the real demographic information from the input. Since the same trigger is attached to all the input, the uniform demographic information contained in the trigger will weaken the dependence of the model on the true demographic information contained in the data, and thus improve the fairness of the pretrained model.

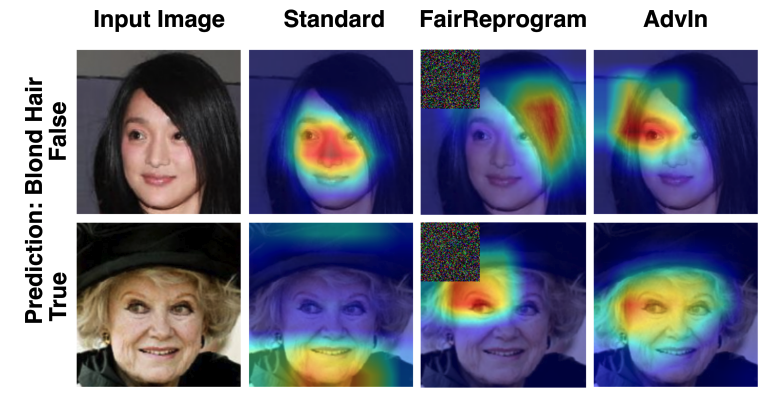

Input Saliency Analysis

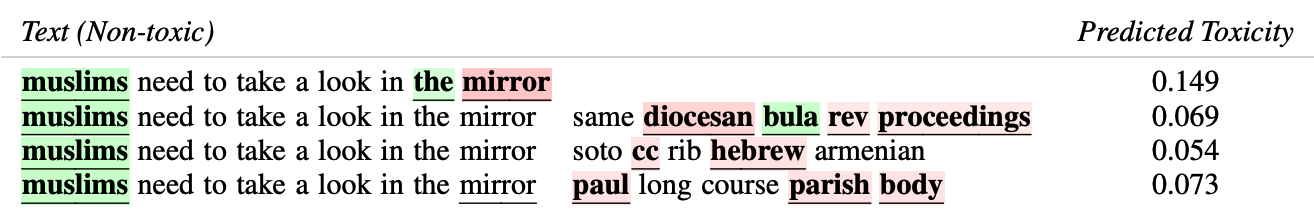

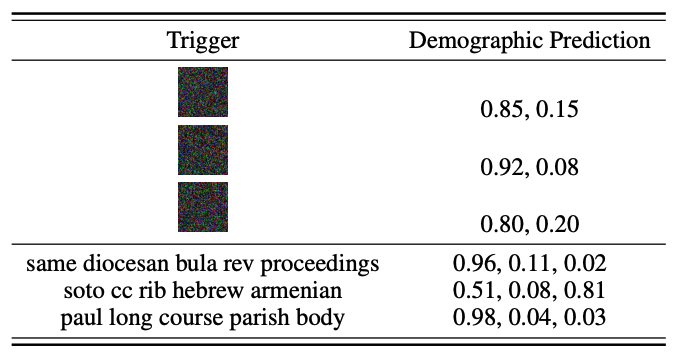

The following two figures compare the saliency maps of some example inputs with and without the fairness triggers. Specifically, For the NLP applications, we extract a subset of Civil Comments with religion-related demographic annotations, and apply IG to localize word pieces that contribute most to the text toxicity classification. For the CV application, we use GradCam to identify class-discriminative regions of CelebA’s test images.

Figure 8 presents the input saliency maps on two input images with respect to their predicted labels, non-blond hair and blond hair, respectively. When there is no fairness trigger, the saliency region incorrectly concentrates on the facial parts, indicating the classifier is likely to use biased information, such as gender, for its decision. With the fairness trigger, the saliency region moves to the hair parts.

In Figure 9, our fairness trigger consists of a lot of religion-related words (e.g., diocesan, hebrew, parish). Meanwhile, the predicted toxicity score of the benign text starting from ‘muslims’ significantly reduces. These observations verify our theoretical hypothesis that the fairness trigger is strongly indicative of a certain demographic group to prevent the classifier from using the true demographic information.

To further verify that the triggers encode demographic information, we trained a demographic classifier to predict the demographics from the input (texts or images). We use the demographic classifier to predict the demographic information of a null image/text with the trigger. We see that the demographic classifier gives confident outputs on the triggers, indicating that they found triggers are highly indicative of demographics.

Citation

1

2

3

4

5

6

@inproceedings{zhang2022fairness,

title = {Fairness reprogramming},

author = {Zhang, Guanhua and Zhang, Yihua and Zhang, Yang and Fan, Wenqi and Li, Qing and Liu, Sijia and Chang, Shiyu},

booktitle = {Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems},

year = {2022}

}

Reference

[1] Ramprasaath R Selvaraju et al. “Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization” ICCV 2017.

[2] Mukund Sundararajan et al. “Axiomatic attribution for deep networks” ArXiv, vol. abs/1703.01365, 2017.

[3] Narine Kokhlikyan et al. “Captum: A unified and generic model interpretability library for PyTorch” arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.07896.